|

Summer 1999 (7.2) |

||||

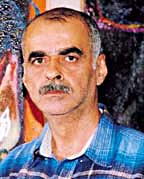

| Hamza

Abdullayev (1946- ) |

||||

Singing

My Song in the Language of Art During his studies in Moscow, Hamza often skipped class to hang out in the studios of dissident artists such as Ernest Neizvestny. When he returned to Azerbaijan, he settled down in Buzovna, a seaside community of young Azerbaijani artists gathered around Javad Mirjavad. |

||||

I've been drawing since I was a child. Our family lived in Baku, on one of the older blocks in the center of the city, near the Taza Pir mosque. My older brother, who was also interested in art, used to bring home reproductions of works by great Italian artists and I would try to copy them. My enthusiasm for the fine arts led me to study at the Azimzade Technical School of Arts in Baku and later at the Fine Arts Institute in Moscow. |

||||

|

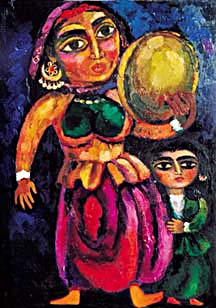

Above left: Hamza Abdullayev, "Woman With Gaval (Tambourine)", 100 x 73 cm, oil on canvas, 1992. Above right: Hamza Abdullayev, "Red Camel", 90 x 70 cm, oil on canvas, 1993.

Above left: Hamza Abdullayev, "The Path to the Sea", 80 x 100 cm, oil on canvas, 1996. Above right: Hamza Abdullayev, "Two Ships", 100 x 65 cm, oil on canvas, 1994. Social Realism During the 1960 I tried to incorporate these new ideas into my work. Of course, my teachers didn't like this, and I often had quarrels with them. For example, in the second year, we were taught to paint still lifes. Using a technique introduced by the French artist Fernand Léger [1881-1955], I painted the objects in my still life with pure colors and outlined them with thick dark lines. The teacher approached me angrily and said, "What are you doing? What is this that you're painting?" I answered him in the passion of youth, "I see things this way and I'm going to paint the way I see them." After a brief argument, I was expelled from the class. In 1963, I was reinstated in the class of another artist. In the third year, when we were painting a nude, I put two sheets of paper on my easel. When the teacher was around, I painted in the realistic style on the top sheet, but when he was away, I painted as I pleased on the other piece of paper. When the teacher, who happened to be a weak painter himself, found out, he called me to his studio and reprimanded me: "You're a sucker. You're naïve-not aware of anything. Do you understand what period we're living in? You could be arrested." So I was obliged to leave that class, too.  There were some very ridiculous incidents. For example, Golomshtak and Sinyavsky published a book about Picasso in Moscow. But afterward, those dissident authors had to leave the USSR. I had torn out the reproductions from their book and pasted them into my notebook. The pages contained the well-known artists' opinions about art as well as the titles of books by Sigmund Freud and Friedrich Nietzsche. (These books were forbidden, as were works by Sartre, Kafka and several other authors.) Left: Hamza Abdullayev, "White Camel", 90 x 73 cm, oil on canvas, 1993. During a lesson, our teacher saw me looking at this notebook. He took it from me and held it up. Raging with anger, he exploded, "Look here, comrades, the Soviet country is feeding Hamza, but Hamza is looking at the works of capitalist artists and reading Freud and Nietzsche. Besides, he is not a member of the Communist Youth Organization." Some time later, the Director of Studies Agabala Muallim (who was a good guy indeed) came to my home and told my mother, "Your son Hamza has to change his manner of thinking. He draws a fork but claims that it's a ballerina." He meant that I wasn't following the school of Social Realism and was creating symbolic art instead. But I refused to change. As a result, I flunked three exams and failed a grade. Instead of studying for five years at the Institute, it took me six. That was the first major blow that I received from the Soviet system. Living in Buzovna Alovsat Aliyev studied with me in the School of Arts in the 1960s. He was from Buzovna. Afterward, he painted beautiful landscapes of the village where he grew up. We were very close friends, and I would often go to his place in Buzovna. (I regret to say that this talented artist died in his early forties.) That landscape is etched in my memory forever: houses lost in the sand, wells full of salty water, old fishermen's boots on the shore, rocks like fantastic old dragons, strong winds blowing from the sea, fig trees that looked as though they bent their heads to the sand in the face of the strong winds off the Absheron peninsula, stone walls, vineyards and roads that stretched to the sea. Absheron and everything related to it became the main theme of my creative activity. With Alovsat's help, I repaired an old tumbled-down house near the seashore and lived there. We called that house "The House of Sands." There were enormous sand dunes in the area and the view was wild and fantastic. Strong winds were always blowing. At night, it was difficult to sleep because of the sound of the waves crashing against the rocks. During the 1960s and 1970s, the great Azerbaijani artist Javad [Mirjavad] lived and worked in Buzovna in "Altay's Cottage." His works and our personal contact played a critical role in my maturing as an artist. Javad's discussions about art and his mode of life set an example for me; I consider him to have been one of my most important role models. Other artists who were his age were already members of the Artists' Union. They had already gained their "reputations" and were dutifully serving the Communist regime with their works. But Javad never bowed to the Artists' Union. Despite his financial difficulties, he continued living in Buzovna. His tenacity reminded me of the epic heroes in Azerbaijan's fairy tales. He was of that generation of Ernest Hemingway [American writer], Nazim Hikmat [Turkish poet] and others. I was a very romantic guy. My brain was crammed with Eastern legends: jinns, dragons and magic carpets. Good and evil forces were real notions for me. Sometimes on moonlit nights, I could see all of those things in the sandy place where I was living. Once I asked Javad, "Have you ever seen jinns?" He answered me very seriously that he had. He told me that there were some jinns living in the domed bathhouses in Fatmayi [a village in Baku] and that it was very risky to go there at night. Those years at Buzovna were wonderful and unforgettable moments of my life. I considered Javad my mentor and it was the beginning of the creation of what came to be known as the Absheron School of Arts. This group included the youth who knew Javad very well, those who were in contact with him and either living in Buzovna or visiting frequently. At the head of the Absheron School of Arts stood Javad himself, as well as his friends, well-known artists like Rasim Babayev, Gorkhmaz Afandiyev and Togrul Narimanbeyov. The entire group of today's major artists in Azerbaijan are somehow connected with this school. It's part of their genetic roots and they have all derived advantages of their association with it despite the fact that afterwards, they all went their own ways. Study in Moscow In 1968, I went to study at the Moscow Fine Arts Institute. The tedious lectures and seminars there bored me. I became fed up with classes like Political Economy and Party History that had nothing to do with art. I skipped class to visit museums and become more familiar with the world of artists and musicians in the city. Those years were very hard for artists. A shocking incident had occurred in Moscow; afterward it became known as the "Bulldozer Exhibition." Dissident artists who were against the Soviet system and had not been allowed to exhibit their works for years had managed to organize an open-air exhibition in Moscow. The KGB and Communist party officials found out about it right away and sent bulldozers in to destroy the exhibition. The artists were branded as "formalists," "abstracters" and "charlatans". "Formalist" meant that they used ways of expressing their thoughts that were different from the prescribed Social Realism method. "Charlatans" was a curse that referred to artists who went against the system. The Soviet people were urged not to accept these dissident artists. Hostile speeches by Ilichov, the secretary of ideological affairs of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, were published in newspapers like "Pravda" (Truth) and "Izvestiya" (News). At the time, there were two kinds of art: official Soviet art, which was supported by the Communist Party, and what could be called "real art", which was created in cellar studios. Enormous paintings promoting the Soviet system were on display in the "Manege" central showroom. Those pictures, which were very weak from a professional point of view, depicted stumpy, broad-shouldered miners, participants in parades holding the Soviet flag high, rosy-cheeked collective farmers, statesmen and party leaders. Real artists were not allowed to exhibit and had to organize shows in their own apartments. Later, many of them immigrated to Western Europe and America. One of these dissident artists who escaped from the USSR was sculptor Ernest Neizvestny. After the "Manege" exhibition in Moscow, he was targeted by Khrushchev, the Politburo and other government officials. I enjoyed visiting his studio, learning from him as he showed his works to me. Once he told me jokingly: "It looks like the center of world art has been transferred from Paris to Baku." Of course, after my contact with artists like Ernest, lectures back at the Institute held no interest for me. Finding His Roots I missed Absheron very much, so I decided to leave the Institute in Moscow. My mother didn't want me to leave, so I continued my study via correspondence courses. In 1979, I returned to Baku. I wanted to find my own path as an artist, to find my own roots. My search for individuality helped me become more familiar with ancient monuments, Eastern art and Azerbaijani applied art. I explored the mystery of the stone monuments scattered throughout the region as well as the beauty of the "white camel" in the Sufi Hamid cemetery (not far from Baku). The creative languages of miniatures, the artists of the Gajar period and the unknown creators of ancient grave monuments impressed me. In these works, I saw other styles, other ways of expression that were quite different from those found in European art. This style was very familiar to me as an Easterner and as a person with a Turkic background. I support nationalism in art. When I say "nationalism", I don't mean Eastern ornaments or national clothes. Nationalism runs in one's blood and is embedded in one's memory. Of course, this way of thinking overstepped the boundaries of official Soviet ideology and was not supported by the leaders of the Artists' Union. Artists my age went to constructions, collective farms and Party Congresses. They did paintings from nature, creating very dull works, and yet had exhibitions and received honorary titles and prizes from the Komsomol. Their portraits of party leaders and statesmen hung in exhibitions as examples of great art. In one large exhibition, there were about forty portraits of Leonid Brezhnev painted by Azerbaijani artists. Another exhibition featured portraits of Heroes of Socialist Labor. The government paid the artists well for these works. During the 1970s and 1980s, a large group of Azerbaijani artists competed for honorary titles, prizes and cheap fame. Most of them forgot what real art was all about. Cost of Dissidence In 1981 I wanted to get married, but was in serious financial difficulties. Since I had to earn money to pay for my wedding, I went to the Artists' Union and asked them to buy some of my works. So I brought some of my paintings to the Union and left them there. But nothing came out of it. I got married anyway with the help of my relatives. But in 1983, the marriage ended in divorce. Even though two years had passed, not one of the works I had left at the Artists' Union had been sold. The late artist Gorkhmaz Afandiyev told me, "You know what? The chairman of the Artists' Union is waiting for you to get tired of going back and forth [to check on your paintings]. He's hoping that you'll just give up." The chairman of the Artists' Union called me into his study and told me, "The party doesn't allow us to paint this way. That's why we can't accept your works." That was the atmosphere of the 1970s and 1980s. Artists were dependent on Soviet cultural institutions. Those who bowed before the totalitarian regime had everything they wanted. They were given honorary titles, prizes, new apartments before it was their turn, cars, etc. These honorable "artists" looked down on dissident artists. The great artist Ashraf Murad was one of the dissident artists who faced cruel injustices. In 1979, after Ashraf's death, the people's artist who had declared himself the owner of his studio had Ashraf's works burned. Another dissident was the songster of Old Baku-Alakbar Rezaguliyev. He painted his inimitable "Old Baku" series after being in prison for 28 years. He had been arrested as a political prisoner. Plus there was Kamal Ahmad's studio-Kamal Ahmad was one of those who had his own special place in Azerbaijani art. His studio was located in the damp cellar of the Artists' Union building. Javad Mirjavad had no studio of his own, so he worked out of his home. Why Create? Art is my life! My life and everything that surrounds me arouses deep feelings in my heart. If I couldn't transfer these feelings onto canvas, life would lose its meaning for me. If I couldn't create, then I couldn't live. Perhaps creating is like a biological process or like God's creation of mountains and valleys. Exceptional works are those that were created by Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Ashraf Murad and Javad Mirjavad. These works were created as a result of hard labor and a rejection of the blessings of life. Those who created these works put their hearts into them. It's no wonder Javad Mirjavad used to say: "Art is killing me." I carry the plot of every work in my heart and thoughts for a long time and let it nourish and grow there. I work on each canvas for a long time, as though I want to lay open all the images and meanings hidden in its depth. I want to show life as it is, with all its contradictions: delight and tragedy, beauty and ugliness. I want to create works that are like the nuances of our traditional modal music, the mugam [pronounced moo-GAHM]. When I'm working on a canvas, I try to expend all of my talent and strength as if were the last work of my life. Today, most artists are working for the commercial market. When I'm creating my works, however, I never think about whether I'll be able to sell them or not. When my work is in progress, I'm like a man surrounded by darkness seeking the light. And the light I am longing for is the light of Truth. If the work turns out right, if I have been able to sing my song in the language of art, I feel at ease. It's a joy that I cannot describe in words because life is fleeting, art is eternal.s, artists in the USSR were compelled to follow the style known as "Social Realism". Art was meant to reinforce Communist ideology and the Soviet mode of life. Those who wanted to create through symbolic approaches were branded as "formalists" and their works were not allowed to be displayed at exhibitions, nor did they receive government orders and commissions. Such artists had to work in secret and keep their works hidden. All of the works that did not meet the approval of the Soviet system were taken away, even from museums, especially when we were under the totalitarian rule of Stalin. At art school, we were taught "Social Realism" in a Russian academic manner. But already as a second-year art student in 1962, I was interested in the works of European artists like Cézanne, Van Gogh, Matisse and Picasso. Van Gogh's letters, reflecting his thoughts about art, were like revelations for me. Despite my teachers' strong objections, I would spend hours at the library, reading books about contemporary art and looking at rare and forbidden reproductions. Hamza Abdullayev can be reached in Baku at (99-412) 95-67-15. From Azerbaijan International (7.2) Summer 1999. © Azerbaijan International 1999. All rights reserved. |