Summer 1999 (7.2)

Sattar

Bahlulzade

(1909-1974)

The Vibrant

Pulse of Nature

by Ziyadkhan

Aliyev

Sattar Bahlulzade (pronounced

sat-TAHR bah-lul-ZAH-deh) was known for his unpredictability,

but no one anticipated such a volatile reaction to criticism.

The occasion was the opening of a new exhibition at the Baku

Art Museum. Sattar had submitted one of his paintings-a view

of the sea-but the work had been rejected. One of the organizing

committee members told him that he had "misinterpreted"

nature and that his painting needed more work.

Sattar Bahlulzade (pronounced

sat-TAHR bah-lul-ZAH-deh) was known for his unpredictability,

but no one anticipated such a volatile reaction to criticism.

The occasion was the opening of a new exhibition at the Baku

Art Museum. Sattar had submitted one of his paintings-a view

of the sea-but the work had been rejected. One of the organizing

committee members told him that he had "misinterpreted"

nature and that his painting needed more work.

"You people paint landscapes without even leaving your studios,"

Sattar shot back. "You just copy from postcards and photographs.

I don't think you even know what nature looks like!" Suddenly,

he kicked his painting, damaging it, and stomped off.

This confrontation, which happened in the 1950s, illustrates

Sattar's passion to create art on his own terms. As one of the

first Azerbaijani artists to break away from the government-mandated

style of Social Realism, he is known for developing his own unique

style of painting landscapes. Though he passed away 25 years

ago, his 90th Jubilee will be celebrated this year (1999) in

Baku.

![]() Sattar

began his professional education at the National Art Institute

in Baku (1927-1931). Then he worked with Azim Azimzade at the

newspaper called "Communist" for the following two

years. In 1933, acting on Azimzade's advice, he went to Moscow

to continue his education in the Drawing Department at the Moscow

Fine Arts Institute. There he studied in the studio of V.A. Favorsky.

During the summer workshops in Crimea, Russian painter Marc Chagall

saw some of Sattar's sketches and suggested that he transfer

to the Institute's Painting Department. So he did.

Sattar

began his professional education at the National Art Institute

in Baku (1927-1931). Then he worked with Azim Azimzade at the

newspaper called "Communist" for the following two

years. In 1933, acting on Azimzade's advice, he went to Moscow

to continue his education in the Drawing Department at the Moscow

Fine Arts Institute. There he studied in the studio of V.A. Favorsky.

During the summer workshops in Crimea, Russian painter Marc Chagall

saw some of Sattar's sketches and suggested that he transfer

to the Institute's Painting Department. So he did.

In 1940, Sattar worked on "Babak's Revolt" as his final

project. (Babak refers to the 7th-century figure who is considered

a great hero in the region because he led a resistance against

the Arabic invasion. Eventually he was captured and executed.)

Even though Sattar exhibited this work, he didn't have a chance

to defend his diploma because World War II broke out in 1941

and he had to remain in Baku. After the war was over, he received

several invitations from Moscow to return to defend his diploma,

but he never did. "Does an artist need a diploma to prove

his worth?" he asked.

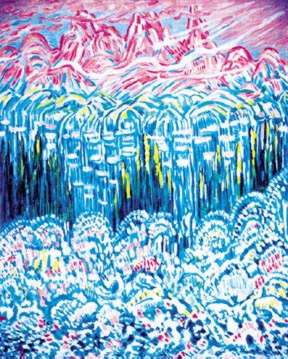

Sattar Bahlulzade, "Outside the Village of Laza".

Back

to Nature

Most of Sattar's life and creative activity were spent in Amirjan,

a village about half an hour's drive east of Baku near the sea.

Like the character of Majnun in the Eastern legend of "Leyli

and Majnun," Sattar spent most of his time outdoors in nature,

rarely going into the city or seeing his friends and family.

Majnun wandered throughout nature because he was lovesick; Sattar

was trying to grasp nature's beauty and capture it on canvas.

He never married and didn't have much of a personal life, but

those who close to him got used to his eccentricities.

Though he experimented in various genres of art, his unique talent

was landscape painting. At first, he used to paint nature realistically

as he had been taught. But soon he developed his own style to

express the emotional feeling it invoked in him. This new style

was more surreal and cosmic-in fact, some of his paintings are

reminiscent of photos of the earth taken from space. Using a

combination of pastel colors and bold strokes, he made nature

look more colorful and lively, and sometimes even more fantastic,

than it did in reality.

A New

Style

![]() Sattar's

ability to closely observe things enabled him to create subtle,

sophisticated renderings of nature. He would gain delight from

the bits of beauty that were expressed in stones, trees and flowers-a

scene that might seem quite ordinary to other people. He would

then transfer his delight onto canvas so that others could enjoy

it as well.

Sattar's

ability to closely observe things enabled him to create subtle,

sophisticated renderings of nature. He would gain delight from

the bits of beauty that were expressed in stones, trees and flowers-a

scene that might seem quite ordinary to other people. He would

then transfer his delight onto canvas so that others could enjoy

it as well.

One such experience gave birth to his painting "The Tears

of Kapaz." In 1962, Sattar was traveling with his artist

friends Tahir Salahov and Togrul Narimanbeyov. They stopped in

Ganja to see Goygol and Kapaz. (Kapaz is a nearby mountain. In

the 12th century, a strong earthquake in the region created a

cascade of lakes, including Goygol and Maralgol.)

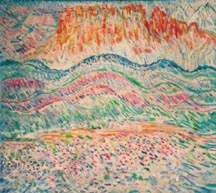

Sattar Bahlulzade, "The Shamakhi Vineyards". Courtesy:

Private Collection of Paola Parviz.

Kapaz was very misty the day that they happened to be there and

Sattar was quite impatient to see the sun rise behind the mountain.

The following morning, he witnessed the sun rising while the

moon was still shining down from the other side of the mountain.

The scene impressed him so much that after they returned to Baku,

he tried to recreate his emotions by painting the scene.

Another work, "The Wish of the Land," was inspired

by a visit to Lake Jeyranbatan that same year. This lake supplied

Baku with fresh water. Rumors were spreading that the lake was

drying up, so Sattar decided to go there and have a look for

himself. While walking around, he noticed a tiny flower growing

out of the dry parched land. He sensed how much the flower was

longing for that deserted land to become a flowery meadow. Back

in his studio, he painted "The Wish of the Land." The

work seems to say, "Where there is water, there must be

beauty."

As the founder of contemporary Azerbaijani landscape painting,

Sattar loved to travel around the country exploring its beauty.

Once he remarked, "I don't need to go to Tahiti like Gauguin.

Others don't need to either. My inspiration comes from my own

country and people."

Many of his works depict specific areas of Azerbaijan. For instance,

"Bazarduzu Outskirts" features Bazarduzu, the highest

point of the Grand Caucasus Mountains. Other examples include

"Old Shamakhi" and "Autumn in Nakhchivan."

Each one tries to show the tension that exists between humanity

and nature. But of all Azerbaijan, Sattar loved his native village

Amirjan the most and had no desire to leave it. When he was allocated

a two-room apartment in the "House of Painters" in

Baku, he gave the apartment to his friend Tahir Salahov.

A Singular

Character

![]() Sattar

was known for having several unique traits; one of them was his

very long hair. It is said that he cut it only twice during his

lifetime. The second time was in 1973, during a serious illness.

The first time took place when Azerbaijani sculptor Fuad Abdurrahmanov

decided to make a statue of Sattar. The artist suspected that

Fuad was more infatuated with his long hair than with his personality,

so he showed up in Fuad's studio having cut off his hair. Needless

to say, Fuad was quite surprised. Today the white marble statue

commemorating Sattar depicts him with short hair. The statue

is on display at the National Art Museum.

Sattar

was known for having several unique traits; one of them was his

very long hair. It is said that he cut it only twice during his

lifetime. The second time was in 1973, during a serious illness.

The first time took place when Azerbaijani sculptor Fuad Abdurrahmanov

decided to make a statue of Sattar. The artist suspected that

Fuad was more infatuated with his long hair than with his personality,

so he showed up in Fuad's studio having cut off his hair. Needless

to say, Fuad was quite surprised. Today the white marble statue

commemorating Sattar depicts him with short hair. The statue

is on display at the National Art Museum.

Sattar Bahlulzade. Courtesy: Private Collection of Paola Parviz.

Sattar was also known for his generosity. He often gave his paintings

away to people who admired them. Foreigners who came to Azerbaijan

who were interested in art would usually visit Sattar's studio.

(Though the officials disliked this, they couldn't go against

the guests' wishes.) Once an Italian wanted to buy one of his

works. Sattar decided to give the work to him instead. The Italian

hesitated, "I can't accept such a valuable work without

giving anything in return." Sattar answered, "I never

give cheap presents." That put an end to the discussion.

An exhibition of Sattar's works was held at the Prague National

Gallery in 1964. After the exhibition, five of the works were

selected for inclusion in the museum's permanent collection.

Sattar refused to accept an honorarium for the works, offering

them as presents to the Gallery. These stories of his generosity

correspond to his simple lifestyle. He was known for not caring

about material things like money, clothes or anything but the

cheapest of cigarettes.

State

Prize Refused

Sattar won many prizes for his art. He received the title of

Honored Art Worker of the Republic in 1960 and was named People's

Artist in 1963. When he won the State Prize in 1972, however,

he refused to accept it. When the prize money arrived at his

home in Amirjan, he sent it back.

He was upset because his efforts to meet with the Secretary of

the Communist Party in Azerbaijan, Heydar Aliyev, had been unsuccessful.

Sattar had wanted to tell him about the general problems of artists

in Azerbaijan. Only when he threatened to move to Georgia did

his friend Tahir Salahov manage to set up the desired meeting.

(It would have been considered a scandal if an artist of Sattar's

stature had left Azerbaijan.)

When Tahir and Sattar arrived at the meeting, the Secretary for

Cultural Affairs was there as well. He extended his hand to Sattar,

who coldly refused it-a gesture of extraordinary disdain at the

time. (The Secretary had been the one who prevented Sattar from

being able to meet with Aliyev.) After a productive meeting with

Aliyev, Sattar agreed to accept the State Prize money and again

exhibit his works in Azerbaijan.

Speaking

Up

![]() In

the 1970s, an important exhibition, "The Achievements of

Soviet Azerbaijan," was to be held in Baku. One of the Full

Members of the Politburo Fyodr Kulakov was to come from Moscow

to attend the event. Well-known Azerbaijani artists were commissioned

to decorate the hall.

In

the 1970s, an important exhibition, "The Achievements of

Soviet Azerbaijan," was to be held in Baku. One of the Full

Members of the Politburo Fyodr Kulakov was to come from Moscow

to attend the event. Well-known Azerbaijani artists were commissioned

to decorate the hall.

The government was supposed to supply the artists with materials

to make the banners and coats of arms. Instead of natural silk,

the artists were given artificial silk. It was impossible to

paint because the colors wouldn't soak into the material. So

the decorations looked awful.

The day before the opening ceremony, the government officials

arrived at the exhibition to give their official approval. Seeing

the inferior quality of the decorations, they started blaming

the artists, who remained silent for fear of losing their government

commissions.

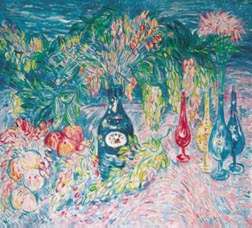

Sattar Bahlulzade, "Still Life". Courtesy: Private

Collection of Paolo Parviz.

Sattar was there among the artists even though he had not been

invited to participate. He burst into anger and accused them

for keeping silent. He told them that Stalin had killed Husein

Javid [an outstanding poet], but Javid was not dead-he still

lived in his poems. Sattar knew that even though the people in

power still carried out Stalin's aims, they didn't have the power

to kill like Stalin had had. Sattar urged the artists to stand

up and explain what the real problem was.

Illness

and Death

In 1973, Sattar fell extremely ill with a case of blood poisoning.

Even though he received treatment at a hospital in Sabunchu [a

district in Baku], he didn't recover. The head doctor of the

hospital said that the only other option was for him to be treated

in Moscow. But the officials didn't want to cover the financial

expenses of such a trip, so Sattar's friends made arrangements

to organize the trip for him. Gulmurad, who ran a local teahouse,

took him to Moscow where he underwent the operation successfully.

When Sattar passed away in 1974, he was not buried in the Avenue

of the Honored Ones as might have been expected. Instead, according

to his will, he was laid to rest in his native village of Amirjan,

next to his mother's grave. The monument on his grave-a statue

of Sattar standing and holding two empty picture frames-was made

by Omar Eldarov. Today, a bronze bust of Sattar stands in front

of the Amirjan Cultural House and a street in Baku takes his

name as well.

Sattar's legacy includes countless works that have been exhibited

all over the world, including personal exhibitions in the U.S.,

England, Turkey and Russia. He also created around 30 sketch

diaries that contain his reflections on life and art.

To find out

more about Sattar Bahlulzade's works, contact Sattar's nephew

Rafael Abdinov in Amirjan at Tel: (99-412) 20-08-73.

From Azerbaijan International (7.2) Summer 1999.

© Azerbaijan International 1999. All rights reserved.