|

Summer 2000 (8.2)

Street Scenes

from Yesteryear

The Prints

of Alakbar Rezaguliyev

(1903-1974)

Was it nostalgia? Or

was Alakbar Rezaguliyev (pronounced a-lak-BAR re-za-gu-LI-yev)

just plain homesick for the pre-Soviet Baku of his childhood?

His black-and-white linoleum prints of Ichari Shahar (Inner City)

definitely harken back to earlier, simpler days. Was it nostalgia? Or

was Alakbar Rezaguliyev (pronounced a-lak-BAR re-za-gu-LI-yev)

just plain homesick for the pre-Soviet Baku of his childhood?

His black-and-white linoleum prints of Ichari Shahar (Inner City)

definitely harken back to earlier, simpler days.

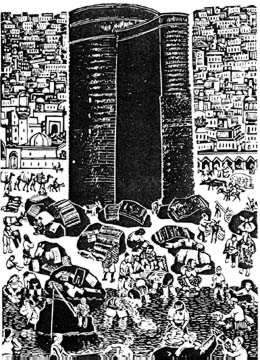

Ordinary people carry out ordinary activities: women wash carpets

on the shore of the Caspian in the shadow of the Maiden's Tower,

farmers transport loads of grain and hay, farmers shoe their

oxen, a man stands in front of three heavily veiled women - all

of them his wives.

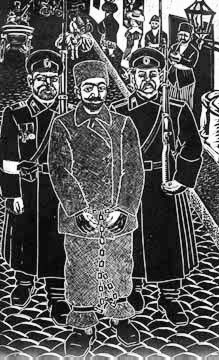

Left:

Water Carrier

in early 20th century by Alakbar Rezaguliyev

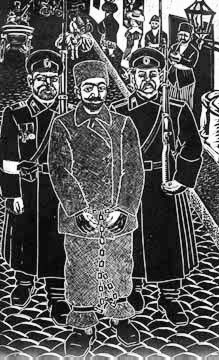

The world pictured in these prints was turned upside down when

the Red Army took over Baku in 1920. Alakbar was affected by

the revolution as much as anyone, as he was among the first to

be arrested in what would later be termed as Stalin's Repression,

in which 70,000 Azerbaijanis were executed or exiled along with

hundreds of thousands of other citizens throughout the USSR.

Alakbar spent more than 23 years of his life in exile. His prints

of early Baku - while lighthearted and fun - may have been the

only way he could escape the feelings of victimization brought

on by the Soviet system.

_____

Alakbar Rezaguliyev was born on January 31, 1903 in Baku. He

studied at Moscow Technical Art College from 1925 to 1928, then

returned to Baku just after graduation.

Soon afterwards, he

was arrested along with his friend, a sculptor named Ibrahim.

His friend was accused of advocating "pan-Turkish ideas,"

and Alakbar was deemed guilty by mere association. When Alakbar

was thrown into prison, he didn't even know what he was being

accused of or why. Soon afterwards, he

was arrested along with his friend, a sculptor named Ibrahim.

His friend was accused of advocating "pan-Turkish ideas,"

and Alakbar was deemed guilty by mere association. When Alakbar

was thrown into prison, he didn't even know what he was being

accused of or why.

Left: Lamplighter.

He was sentenced to six years. After being released, he returned

and married Sona Huseynova in 1935; the couple had two daughters,

Adila and Sevil. He and Sona later divorced.

On November 3, 1937, again Alakbar was arrested. Rasim Babayev,

a fellow artist, says that Alakbar told him how it happened:

"One day I was walking down Komsomolskaya Street when I

ran into Ruhulla Akhundov (one of the Bolsheviks who helped establish

the Soviet system in Azerbaijan).

Ruhulla looked annoyed at seeing me and remarked rudely: 'Hey,

you dumb guy, are you back here again?' And with those words,

I was sent directly back to prison" - this time, to Siberia

and later on to Solovki an island in the Arctic where there are

monasteries. Alakbar would go on to do a series of paintings

depicting the isolation of those years there.

The stories Alakbar told Rasim about his exile were dismal at

best. While in Arkhangelsk (a city in Russian on the northern

coast of the Arctic Ocean) by pure accident he was placed in

a basement together with some White Guards.

In the morning, a warden came and called

the roll. All of the Guards were taken out to be executed. Only

Alakbar's name was not called. "The warden got quite confused,

looked at me and asked, 'Hey, you guy, who are you? Why are you

still sitting here?' I replied: 'I'm an artist. You didn't call

my name.' The warden was astonished and hit me, saying, 'Get

lost, you!' In the morning, a warden came and called

the roll. All of the Guards were taken out to be executed. Only

Alakbar's name was not called. "The warden got quite confused,

looked at me and asked, 'Hey, you guy, who are you? Why are you

still sitting here?' I replied: 'I'm an artist. You didn't call

my name.' The warden was astonished and hit me, saying, 'Get

lost, you!'

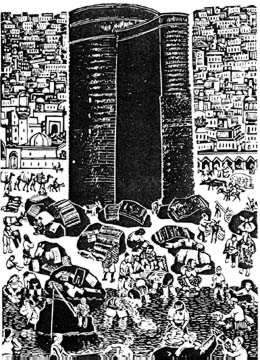

Left: Man with his three

wives at the turn of 19th century in Baku.

And that's how I was sent on to Solovki, a place of no return.

I was nearly starving there but soon started eating birds' eggs

until the priest at the monastery noticed. 'My son, don't you

know that what you are doing is called blasphemy? Who are you,

my son?'

When I told him, he invited me to come and live with them at

the monastery. So I agreed and started to work and live there.

But it didn't last long and soon I was sent off to work in a

sawmill where I injured my finger. That was in Taiga from where

no one escaped and everyone was doomed to death."

During his exile, Alakbar married a German girl named Berta,

who had been sent to Siberia from a German settlement in the

Saratov Autonomous Region.

When World War II broke out, Stalin had exiled all Germans living

in the Soviet Union. Alakbar and Berta had two sons, Ogtay and

Aydin, and a daughter, Sevda.

After Stalin died in 1953, tens of thousands of prisoners were

released from prison. Alakbar, too, was among those who eventually

was able to return to Azerbaijan.

|

|

Left: Prisoner of Solovki.

Rezaguliyev himself was a prisoner and served at Solovki near

the Arctic Circle. He was released after Stalin's death (1953).

Right: Washing carpets in the

sea next to Maiden's Tower.

Aydin Rezaguliyev, a son from his father's second marriage, remembers

his father as a solemn person: "The exile greatly affected

my dad's personality. He became very serious. You can see it

in his photos: in early photos, he was always smiling, but after

he was exiled - never. He was morally broken. It even affected

his creative activity. He very seldom used colors after he came

back."

Above: Street musicians by

Alakbar Rezaguliyev.

Babayev recalls that Alakbar was very careful not be associated

with anyone who criticized political leaders - even in jest:

"Once in 1964, during Khrushchev's period, I remember I

was in the studio of Fazil Najafov, a well-known sculptor, drinking

beer with artists Javad MirJavad and Sattar Bahlulzade. We saw

Alakbar passing by and invited him in.

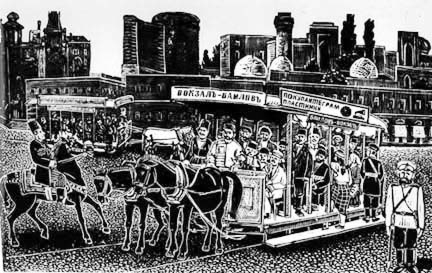

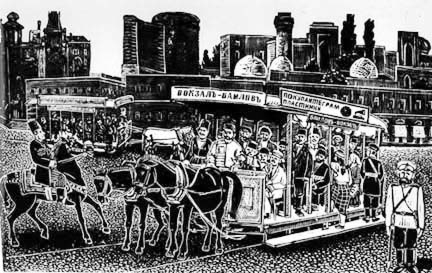

Above: Horse-drawn trolley

at the beginning of 20th century in Baku. Prints by Alakbar Rezaguliyev.

"Javad started to praise him, saying 'Alakbar, you're our

talented artist, and we're proud of you.' But then Javad changed

the subject and started cursing Lenin and Stalin. Alakbar immediately

sprang to his feet and started to leave. Javad begged, 'Alakbar,

don't leave. I won't swear anymore.' But a few minutes later,

Javad broke his promise and again started cursing - this time

against Khrushchev. Alakbar jumped up and left abruptly, apologizing,

'I don't feel like listening to these things. Goodbye.'"

Above: Aydin Rezaguliyev,

son of Alakbar Rezaguliyev in his studio in Baku.

The harsh experiences of imprisonment that he had suffered for

more than two decades, after all, had been his fate merely through

association and not based on any crime that he had ever committed

himself.

Alakbar Rezaguliyev's work can be seen

at the studio of his son Aydin. Tel: (99-412) 39-44-19.

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.2) Summer 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

AZgallery Artists

|

In the morning, a warden came and called

the roll. All of the Guards were taken out to be executed. Only

Alakbar's name was not called. "The warden got quite confused,

looked at me and asked, 'Hey, you guy, who are you? Why are you

still sitting here?' I replied: 'I'm an artist. You didn't call

my name.' The warden was astonished and hit me, saying, 'Get

lost, you!'

In the morning, a warden came and called

the roll. All of the Guards were taken out to be executed. Only

Alakbar's name was not called. "The warden got quite confused,

looked at me and asked, 'Hey, you guy, who are you? Why are you

still sitting here?' I replied: 'I'm an artist. You didn't call

my name.' The warden was astonished and hit me, saying, 'Get

lost, you!'