Summer 1999 (7.2)

Tahir Salahov

(1928- )

A Hint of Red - Pushing

the Limits of Socialist Realism

by Azad Sharifov and Jean

Patterson

![]() For Azerbaijani painter Tahir Salahov, red is

a color that's best used sparingly. It's great for accenting

specific objects-whether it be naturally red objects such as

chili peppers, pomegranates or books, or objects not normally

associated with red such as an oil tanker, an oil pipeline, a

man's shirt, a windmill or even the Eiffel Tower in Paris. In

Tahir's early work, apart from this touch of red, the remainder

of his canvas was typically spread with neutral tones ranging

from light gray and beige to darker shades of olive, brown and

black. Take away the red, which obviously was associated with

Communism, and the painting loses its dramatic edge.

For Azerbaijani painter Tahir Salahov, red is

a color that's best used sparingly. It's great for accenting

specific objects-whether it be naturally red objects such as

chili peppers, pomegranates or books, or objects not normally

associated with red such as an oil tanker, an oil pipeline, a

man's shirt, a windmill or even the Eiffel Tower in Paris. In

Tahir's early work, apart from this touch of red, the remainder

of his canvas was typically spread with neutral tones ranging

from light gray and beige to darker shades of olive, brown and

black. Take away the red, which obviously was associated with

Communism, and the painting loses its dramatic edge.

Socialist Realism

Tahir's development as an artist starting out in the 1950s was

largely shaped by the Soviet government's mandate-namely, that

all artists should paint according to the style defined as "Socialist

Realism". Socialist Realism insisted that paintings should

mirror "real" life; that is, artists should "paint

what they see." Soviet authorities thought this would facilitate

the ability of the masses to comprehend art. In other words,

artists were not free to use symbolic representations. Colors

and shapes should be realistic. However, the term "Socialist

Realism" also implied that the subject matter that artists

painted would be cheerful, productive, confident and optimistic-not

gray, dismal, depressing or questioning.

But Tahir took this mandate a step further and created his own

style, thereby making his own statement. Today people refer to

it as "Severe Socialist Realism". Tahir's early works,

though realistic, dare to suggest that life was not rosy and

triumphant despite the fact that his themes clearly fell within

the prescribed formula.

![]() As

a young painter, Tahir Salahov knew all too well what could happen

when one confronted the Soviet system. When Tahir was only ten

years old, his father was arrested. At the time, his father was

serving as First Secretary of the Regional Party Committee in

Lachin, a region in southern Azerbaijan. Such scenarios were

repeated thousands of times during those horrendous years of

1937-38 that became known as the years of Stalin's Repression.

Like a black widow that consumes its mate, Stalin and those under

his command eliminated any person of whom they were suspicious,

or in many cases, any person whom they held the slightest grudge

against. The individual had not necessarily committed a crime

against the government though, of course, stories were always

fabricated elaborating such crimes, and the individual was promptly

branded as an "Enemy of the People". Tahir's father

was shot and killed on July 4, 1938.

As

a young painter, Tahir Salahov knew all too well what could happen

when one confronted the Soviet system. When Tahir was only ten

years old, his father was arrested. At the time, his father was

serving as First Secretary of the Regional Party Committee in

Lachin, a region in southern Azerbaijan. Such scenarios were

repeated thousands of times during those horrendous years of

1937-38 that became known as the years of Stalin's Repression.

Like a black widow that consumes its mate, Stalin and those under

his command eliminated any person of whom they were suspicious,

or in many cases, any person whom they held the slightest grudge

against. The individual had not necessarily committed a crime

against the government though, of course, stories were always

fabricated elaborating such crimes, and the individual was promptly

branded as an "Enemy of the People". Tahir's father

was shot and killed on July 4, 1938.

Tahir found refuge in the world of drawing-first, at the Pioneer

Palace and later in Art College. He remembers his first introduction

to art. He had borrowed a book from the library and after reading

it, someone suggested that he draw pictures to illustrate the

story. He kept the book several weeks longer and did just that,

and thus began what turned out to be a very successful career

in the arts. Later on he drew pictures for many books without

prodding from anyone. His first Exhibition was for the Belinski

Library in Baku.

Tahir Salahov, "New Sea",

260 x 260 cm, oil on canvas, 1970.

At first, Tahir's family ties hindered his career. Once as a

first-year student at the Azim Azimzade Art Institute in Baku,

he took part in an Azerbaijan-wide contest of young painters.

Instead of using his own name, he submitted his work to the Commission

via two other artists who signed their names to it. The work

was awarded first prize. It took awhile before the identity of

Tahir as the real painter was learned.

Tahir's dream was to study at the Repin Institute of Fine Arts

in St. Petersburg. But he was not able to gain admittance to

the school, even though his skills were recognized by the Commission.

The issue of his father blocked his entrance. The son of an "Enemy

of the People" could not be enrolled. Determined to get

an education in art, he applied to Moscow to the Surikov State

Art Academy. This time he concealed information about his father

and was successful in gaining admission.

Severe Realism

![]() Tahir

belonged to the generation of young Soviet artists that emerged

in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Being from Baku, he often

chose industrial Azerbaijan as the subject for his early paintings.

He loved the city, Ichari Shahar (Inner City), the ancient Maiden's

Tower, the Caspian Sea and its sandy beaches. He loved watching

the fishermen plying their trade and the courageous workers coaxing

the oil from the earth's depths.

Tahir

belonged to the generation of young Soviet artists that emerged

in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Being from Baku, he often

chose industrial Azerbaijan as the subject for his early paintings.

He loved the city, Ichari Shahar (Inner City), the ancient Maiden's

Tower, the Caspian Sea and its sandy beaches. He loved watching

the fishermen plying their trade and the courageous workers coaxing

the oil from the earth's depths.

In particular, the oil workers at Oil Rocks drew his attention.

Oil Rocks is a settlement built up like an island on wooden piers

out in one of the shallower sections of the Caspian Sea. It marks

mankind's first attempt to extract oil from under a major body

of water-not only in Azerbaijan but in the entire world. Oil

Rocks is nearly 50 years old now, but at the time it was quite

new, having been built only 10 to 15 years before Tahir began

focusing on it.

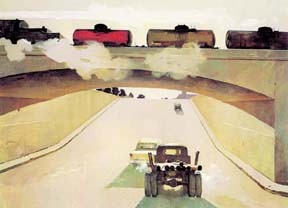

Tahir Salahov, "Morning

Train", 150 x 200 cm, oil on canvas, 1958.

Today, oil workers still live in those dormitories and work in

that isolated, man-made environment. Set against this unsafe

environment of the treacherous seas, the oil workers became the

"heroes" in many of Tahir's paintings. They were strong

and hardworking-fitting symbols of Soviet industrial might. At

the time, the Soviet Union prided itself on its industrialization.

One memorable work is Tahir's "Morning Train" (1958)

which he painted a year after his graduation from the Surikov

State Art Academy in Moscow. His painting shows an industrialized

landscape in which almost everything visible is man-made. Cars

and trucks speed through a highway underpass while oil tanks

pass overhead. Most of the painting is made in neutral shades

of sand and cement, except for one oil tank car, which he painted

red. Visible exhaust coming out of the vehicles heightens the

sense of movement and reinforces the industrial motif. The painting,

with its dull colors and man-made modes of transportation framed

in concrete, lacks the usual warmth of human interaction. Perhaps,

that was part of what the artist was trying to say for those

who cared to understand what was not painted into the picture.

"Morning Train" was exhibited at the 1958 All-Union

Art Exhibition in Moscow, commemorating the 40th anniversary

of the Young Communist League.

Tahir went on to paint many more oil-related scenes over the

following years. Subjects in his paintings include a deserted

oil reservoir ("Reservoir Park", 1959), a group of

three oil maintenance workers on their way to an emergency ("The

Maintenance Men", 1960) and an up-close portrait of an oil

worker ("Oil Worker", 1959). Unlike the scenes found

in paintings following the style of Socialist Realism, Tahir's

workers are not romanticized. Instead, they look serious, tired

and dirty and often uncertain. The world he depicted on his canvases

was not the confident, optimistic microcosm that the Soviets

always tried to present to the world.

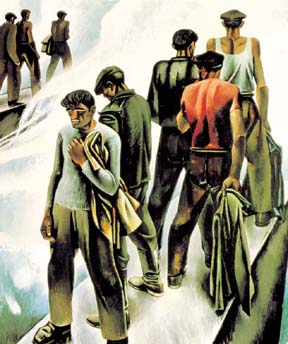

![]() Tahir Salahov, "The Shift is Over",

165 x 368 cm, oil on canvas, 1957.

Tahir Salahov, "The Shift is Over",

165 x 368 cm, oil on canvas, 1957.

Another example of

Severe Socialist Realism can be found in Tahir's painting "Women

of Absheron" (1967). [See the back cover of this issue.]

A group of women stand near the shore, waiting for their husbands-oil

workers-to return home. One assumes that the men live on Oil

Rocks and only get a chance to come home occasionally. Instead

of talking and mingling with one another, as would be expected

of Azerbaijani women, their eyes look vacant, somehow resigned

to their fate with the one exception of the oldest woman, whose

eyes and face are more expressive of the situation. A sense of

loneliness is created by the fact that each woman is looking

off into the distance in a different direction. It's almost as

if the women are statues, islands unto themselves. With their

sullen expressions, they seem to be focused inward, unsure of

the future, unsure of their destinies-separated from their men

and forced to carry the responsibilities of their families on

their own shoulders.

The painting does not show the women happy to be part of the

grand experiment of industrialization and production.

Again, Tahir uses red to accent his painting, this time in two

places: the clothing of the youngest girl and a piece of pipeline

which helps identify the narrative for why the women are gathered

together in the first place. The painting appeared in the 1967

All-Union Art Exhibition in Moscow; it is currently being kept

at Moscow's Tretyakov Gallery.

Tahir's travels abroad also influenced his style. He was one

of the privileged few who got a chance to visit countries such

as Czechoslovakia, France, Spain, Bulgaria, Italy, Mexico, Japan

and the United States and painted many of the scenes that he

saw there. In "The Mexican Bullfight" (1969), Tahir

recaptures a moment from his visit to Mexico. The frame is dominated

by a large, black bull facing off against a matador dressed in

bright red. A few sombreros in the background represent the excited

crowd in the arena. The focus is on the dramatic, ritualized

conflict against what appears as a faceless enemy.

Portraits

Portraits occupy a special place

in Tahir's creative activity. He has painted the portraits of

Azerbaijan's foremost composers-Gara Garayev (1918-1982) and

Fikrat Amirov (1922-1984) along with Azerbaijani poet Rasul Reza

(1910-1981) and Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975),

to name a few. Each portrait reflects Tahir's efforts to draw

out the inner worlds of his subjects.

Portraits occupy a special place

in Tahir's creative activity. He has painted the portraits of

Azerbaijan's foremost composers-Gara Garayev (1918-1982) and

Fikrat Amirov (1922-1984) along with Azerbaijani poet Rasul Reza

(1910-1981) and Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975),

to name a few. Each portrait reflects Tahir's efforts to draw

out the inner worlds of his subjects.

For example, Tahir's portrait of Garayev (1960) stresses the

composer's inner concentration and creativity. [This portrait

may be found in the article "Remembering Gara Garayev,"

AI 6.3, Autumn 1998]. Even though portraits were almost always

painted with the subject facing forward, Tahir established a

side view of Garayev. Once again, the colors are neutral tones,

except for a bright red music book. Garayev's face is plunged

in shadow, as if he has been caught in a moment of deep concentration.

At any moment, it looks like the composer might suddenly stand

up and rush over to the piano to jot down a few bars. This portrait

was awarded the Silver Medal of the USSR Academy of Arts.

Tahir Salahov, "Portrait

of the Russian Composer Dmitri Shostakovich", 136 x 115

cm, oil on canvas, 1974-76.

When Tahir painted Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich's portrait

(1974-76), he took a much different approach. Shostakovich, who

was seriously ill when he sat for the portrait, solemnly gazes

into space with his back to the piano. His frail hands rest on

a red velvet piano stool.

Today, Tahir Salahov lives in Moscow, where he is a professor

and has a studio at the Moscow Art Institute. He has received

numerous honors, including People's Artist of Azerbaijan (1962),

Secretary of the USSR Artists' Union (1968), Member of the Central

Committee of the Azerbaijan Communist Party (1970), Deputy to

the USSR Supreme Soviet (1970), Order of the Red Banner of Labor

(1971), President of the Artists' Union in Azerbaijan (1972),

People's Artist of the USSR (1973) Head of the Studio of Easel

Painting at the Surikov Art Institute in Moscow (beginning in

1974), Full Member of the Soviet Academy of Arts (1975), Order

of the October Revolution (1976), Grekov Gold Medal (1977), Deputy

to the Russian Supreme Soviet (1980) and numerous all-Soviet

and State Prizes for his paintings.

Tahir lives in Moscow and can be

reached at Tel: (95) 201-7274 or Faxes: (95) 243-6551 or 290-2088.

From Azerbaijan

International (7.2) Summer 1999.

© Azerbaijan International 1999. All rights reserved.